Travel, especially when you’re young and going solo, is such a portal into other worlds. That was especially true when, from Summer 1989 to Spring 1990, I went around the world, visiting more than 20 countries along the way. I was, and am, an awfully lucky guy.

One of the best nights on that trip was in Gimmelwald, Switzerland, when several of us were called from our hotel in the snowy mountains to join some locals on a sledding trek. It was exactly as magical as you might think.

(Note: This story originally ran in the April 26, 2001, issue of the Memphis Flyer. The actual sledding occurred on January 27, 1990. And yes, I am a little bit of a details freak when it comes to my life and travels!)

Looking around the dinner table, I saw no one I would have met anywhere else. There were two chirpy girls from L.A., a recovering addict from Santa Monica, a Republican political activist from Missouri, a college kid from Maryland, and me.

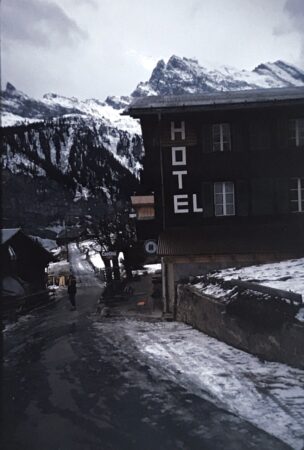

But the important thing was where we were: a little village called Gimmelwald, on top of a cliff in the Swiss Alps, in a hotel that we called — because we couldn’t pronounce its German name — Walter’s. On this winter night Walter had made the few travelers in his place a pot of vegetable soup, and somebody else had brought wine and bread down the hill from Murren, so we were bonding in that particular way that only travelers in a faraway land can bond.

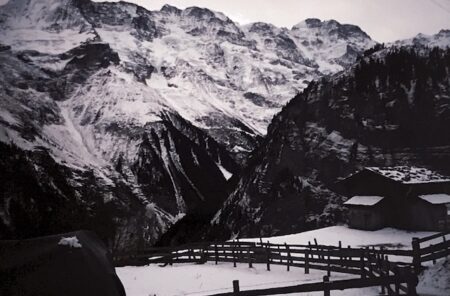

They say Heidi lived in Gimmelwald, but what they mean is that Old Switzerland is alive and well there. There are no cars allowed in the village, and the whole place is designated “avalanche zone,” so developers are not allowed to “develop” it. So instead of tourist shops and fancy hotels, there are cows and winding footpaths and a log cabin from the 17th century. It’s the Switzerland you dream of: green valleys, snow-covered peaks, flowers in window boxes, and little old bearded men inviting you in for a bowl of soup. Rick Steves once said about the place, “If Heaven isn’t what it’s cracked up to be, send me back to Gimmelwald.”

So we sat at Walter’s table and swapped stories and tidbits from the European train circuit: the party hostel in Salzburg, the floating hash bar in Amsterdam, the scenic train from Montreux to Interlaken, the $4, seven-course feasts in Budapest, and the best fish and chips in London. The lines which would have separated us back in the States got blurred, and we met as friends.

There’s a wonderful thing that happens when we leave home; we leave part of ourselves there, too, ideally the masks we normally wear, and given a chance to start fresh for a while, we open up to new possibilities and new people. We find out a little more about who we are, and we’re more willing to share it.

Somebody came in and said the local schoolkids were going sledding and did anybody want to come along? For a moment we all looked at each other, and our eyes said the same thing: “Can this possibly be true? Did somebody just ask us if we wanted to go sledding with a bunch of Swiss schoolkids? Good God, let’s go!”

Yelling thanks to Walter and asking him to save our soup for later, we tumbled out the door in a heap, pulling on hats and gloves, and tore down the hill to the cable car station. Gimmelwald is Old Switzerland, but it’s also a stop on the cable car from down in the valley to further up in the hills. The skiers on their way to Murren barely notice Gimmelwald; most people get it confused with Grindlewald, a resort-filled taste of New Switzerland up the next valley.

The schoolkids wanted to practice their English with us, so we spent the ride up to Murren talking about Madonna and which drugs the recovering addict had done and why Americans don’t know anything about soccer. We also agreed, since this was a mostly male crowd, that it would be an American-versus-Swiss sled race back down the road to Gimmelwald.

Now, about that road. It was a winding, half-hour walk on a one-lane road, with steep hills on both sides — and occasionally stone walls on both sides. A lovely stroll when we first went down it, but one storm later it had become a snow- and ice-covered adventure ride. And now we were going to sled it.

I was paired with the Missouri Republican. We covered the tiny sled entirely. We started, with great excitement, ahead of the other Americans but behind several Swiss.

To steer, such as it was, we would drag our feet on one side or the other. We quickly developed commands — “hard left” and “hard right” or “pick ’em up” for outright speed — as well as a running sports commentary. We were the scrappy Americans trying to shock the sledding world by beating the Swiss on their home hill. At one point, we got it together enough to actually pass somebody and move into third place. The scrappy Yanks took aim at the second-place Swiss sled.

Then we hit the Death Turn — an S-curve covered with ice. The sled suddenly left the ground. We passed that Swiss team, all right, but by then we were going sideways, filling the valley with screams of terror. In the next moment we were somehow tangled together, under our sled, suffering a barrage of Swiss taunting, engulfed in laughter.

We would spend the rest of that night back at Walter’s, trading sledding stories with Swiss schoolkids, and I’ve spent the rest of my life thinking that Heaven probably is a lot like that night in Gimmelwald.

Postscript: If you’ve read or seen much from Rick Steves, you may know this hotel. It’s officially called the Hotel Mittaghorn, but as Rick said, everybody just called it Walter’s. Rick stayed there on his first European trip in the early 1970s, booked the whole place for many tour groups over the years, and when Walter died in January 2020, Rick wrote a lovely remembrance. Rick even got to sled with Walter!